| Citation: Liu Rui-ping, Liu Fei, Chen Hua-qing, Yang Yu-ting, Zhu Hua, Xu You-ning, Jiao Jian-gang, El-Wardany Refaey M. 2024. Arsenic and fluoride co-enrichment of groundwater in the loess areas and associated human health risks: A case study of Dali County in the Guanzhong Basin. China Geology, 7(3), 445‒459. doi: 10.31035/cg2024015. |

Arsenic and fluoride are trace elements affecting human health. Arsenic and fluoride contamination in groundwater, directly harming human health, has developed into a global environmental issue. Long-term exposure to high-concentration arsenic may cause abnormal skin pigmentation, keratinization, conjunctivitis, and even skin and lung cancers. Arsenic has been listed as a Category 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) [International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), 2001]. Fluoride is an essential trace element for the human body. However, insufficient or excess fluoride intake will endanger human health. Specifically, insufficient fluoride intake can cause dental carries and brittle bones, whereas excess fluoride intake can lead to fluorosis (Liu RP et al., 2021). Using groundwater contaminated with arsenic and fluoride for irrigation purposes could endanger crop production and the food chain (Estrada-Capetillo BL. et al., 2014). Over 70 countries and regions in the world, including India, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Viet Nam, Myanmar, and the United States, have discovered high arsenic groundwater (arsenic concentration >10 µg/L) with geogenic characteristics, which affects 140 × 106 people and trends upwards (Li YM, 2021; Chen J et al., 2017). In contrast, high fluoride groundwater (F− concentration >1 mg/L) threatens the health of above 260 × 106 people in the world, including more than 70 × 106 people in China who suffer from endemic fluorosis (Wang YX et al., 2021). Groundwater is identified as a primary medium for human exposure to arsenic (WHO, 2011). In China, 70% of the population uses groundwater as a drinking water source, and two-thirds of cities exploit and use groundwater. To effectively control geogenic groundwater contaminants (GGCs) like arsenic and fluoride, it is necessary to develop a comprehensive strategy that incorporates scientific research, policy development, community engagement, and technical interventions. A crucial objective of tackling these environmental issues is to ensure universal and equitable access to uncontaminated groundwater (Zhang ZJ et al., 2009).

Arsenic contamination in groundwater is severe in some areas of China. Surveys show that endemic arsenic poisoning caused by water intake in China has been identified in eight provinces and cities, influencing more than two million people. Regarding human exposure to groundwater with an arsenic concentration exceeding 50 μg/L (Deng AQ et al., 2017; He XD et al., 2020), Shaanxi Province is one of the hardest-hit areas. In a specific geologic environment, arsenic and fluoride are released in groundwater after migration, and the groundwater with high arsenic and fluoride concentrations is known as primary inferior groundwater, which is characterized by regionality, complexity, and significant correlations between elements (Wang YX et al., 2021). Arsenic is primarily concentrated in sulfide and oxide minerals in nature. Hydrogeochemical processes like adsorption/desorption, dissolution/precipitation, redox, and biogeochemical processes affect arsenic enrichment in groundwater (Zhou YZ et al., 2018; Guo HM, 2014). Fluoride predominantly occurs in igneous and metamorphic rocks, with a small amount observed in sediments formed by fluoride-rich parent rocks. Fluoride in groundwater stems primarily from the weathering and dissolution of fluoride-bearing minerals in primary sedimentary minerals, along with soluble fluoride in soil and aquifer media. Influenced by terrains, dominant factors controlling the migration and enrichment of fluoride and arsenic in shallow groundwater include groundwater depth, alkaline environments, leaching, evaporation, desorption/adsorption, and ion exchange (Dong SG et al., 2022; Wang YY et al., 2022). To effectively protect human health and water resources, it is necessary to employ continuous research, comprehensive monitoring, and sustainable management in response to these environmental concerns (Berger T et al., 2016). In terms of the Quaternary genetic type, the fluoride concentration is significantly influenced by aeolian deposits, while the arsenic and iodine concentrations are primarily affected by alluvial-lacustrine deposits. Principal mechanisms behind the co-enrichment of arsenic, fluoride, and iodine include fine-grained lithologies, gentle terrains, shallow groundwater, alkaline groundwater environments, and microbially mediated mineral dissolution under microbial degradation (Sun Y et al., 2022). The increase/decrease in the arsenic concentration is caused by the dissolution and release/adsorption of manganese oxides due to enhanced/weakened groundwater reducibility. The fluoride concentration is affected by the dissolution of calcium minerals like fluorite in sediments, with high fluoride groundwater occurring in low-calcium and high-sodium environments. Within alluvial-lacustrine deposits, the presence of shallow groundwater is conducive to the enrichment of arsenic and iodine. The dissolution of minerals in these deposits results in the release of arsenic and iodine, while that of manganese oxides affect the arsenic concentration. Furthermore, the breakdown of calcium minerals like fluorite affects the fluoride concentration, especially in the case of low calcium and high sodium concentrations (Ren Y et al., 2021). The fluoride and arsenic concentrations in shallow groundwater affected by rivers are subjected to seasonal changes. Their fluctuations underscore the dynamic characteristics of these contaminants and associated health hazards, necessitating continuous monitoring and management efforts (Yu Q, 2023). Presently, there is a lack of studies on the causes of the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater in loess areas and associated human health risks. Despite advances in insights into these systems, there still exist significant gaps in research, especially on exact factors that lead to the co-enrichment in loess areas. It has been posited that the groundwater in Dali County exhibits high fluoride and arsenic concentrations (Gao YY, 2020). However, related mechanisms and human health risks remain unclear. Additionally, the hydrochemistry of groundwater in the shallow Guanzhong Basin, focusing on the abovementioned aspects, was excluded in previous studies of groundwater hydrochemistry in confined aquifers. Given the current status of studies, it is critical to further investigate the health risks posed by these contaminants and conduct a thorough analysis of the chemical composition of groundwater in confined aquifers. Developing effective methods focusing on these areas of study is crucial for protecting groundwater quality and public health (Gao YY, 2020).

Health risk assessment, the focus of narrow-sense environmental risk assessment, has emerged since the beginning of the 1980s, aiming to link environmental contamination with human health and to quantify the contamination-associated risks to human health. This technique has been globally acknowledged, with its applications having been expanded from the nuclear industry to various fields across many countries. In China, health risk assessment began in the early 1990s, applying primarily to specialized industries like the nuclear industry in its initial stage. As water contamination becomes increasingly severe, more health risk assessments have been conducted for water environments. However, these assessments principally focus on surface water or wastewater reuse, with primary contaminants assessed including inorganics and heavy metals, along with some microbes and organics. With an increase in the degree of water contamination, more extensive aquatic ecosystems have been incorporated into health risk assessment.

Risk assessment originated in the 1930s, dominated by qualitative research. After more than 40 years, the development of the risk assessment system peaked. The U.S. National Academy of Sciences (US NAS) and the US EPA obtained the most abundant achievements. In 1983, the NAS defined public health risk assessment (HHRA) as the characterization of adverse health effects resulting from human exposure to environmental hazards, proposing the four-step method for health risk assessment consisting of hazard identification, dose-response assessment, exposure assessment, and risk characterization. A similar four-step process is also stated in the 1989 Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund of the US EPA, involving data collection and analysis, exposure assessment, toxicity assessment, and risk characterization. Compared to a four-step process of US EPA, the risk assessment model proposed by US NAS in 1983 is more general and suitable for various health risk assessments, with a focus on contaminated sites and the collection of relevant parameters (Gao YY, 2020). Overall, the US NAS’s risk assessment model offers a more general framework applicable to various health risk assessments, whereas the US EPA’s risk assessment model emphasizes operational aspects and data collection from contaminated sites. Health risk assessment serves as a pivotal tool in comprehending the potential repercussions of environmental contaminants on human health. Several notable studies and methodologies have gained insights into this complex interplay.

Wang Z et al. (2011) conducted a comprehensive health risk assessment of arsenic and cadmium in groundwater near the Xianghe River, providing valuable scientific insights for developing regional risk management strategies. Employing the US EPA’s risk assessment model, Su X et al. (2013) assessed the health risks associated with nitrate contamination in groundwater within typical agricultural areas in eastern China.

Zango MS et al. (2019) assessed the health risks associated with fluoride and boron contamination in groundwater to adults and kids based on the hydrogeochemical characteristics of a semi-arid region in northeastern Ghana. Employing geostatistical models, Hossain M and Patra PK (2020) assessed the health risks of micronutrients in groundwater in Birbhum, India. Based on basic theories and methods for health risk assessment of contaminated sites abroad, Chen HH et al. (2006) investigated the problems related to the health risk assessment of contaminated sites in China and the establishment of health risk assessment systems for the contaminated sites. Innovative assessment methods, such as Monte Carlo-based uncertainty analysis and the triangular fuzzy stochastic theory, have enriched risk assessment methodologies, especially in the context of regional groundwater health risk assessment.

A complete health risk assessment refers to an assessment of health risks associated with the ingestion, inhalation, and significant exposure to contaminants in the atmosphere, soils, water, and food chain. This study preliminarily explores the assessment methodology for arsenic and fluoride elements entering the human body through ingestion and skin contact, with a focus on the causes of the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater in loess areas and associated human health risks. Interdisciplinary cooperation will remain crucial in improving risk assessment techniques, aiming to protect public health and achieve evidence-based decision making.

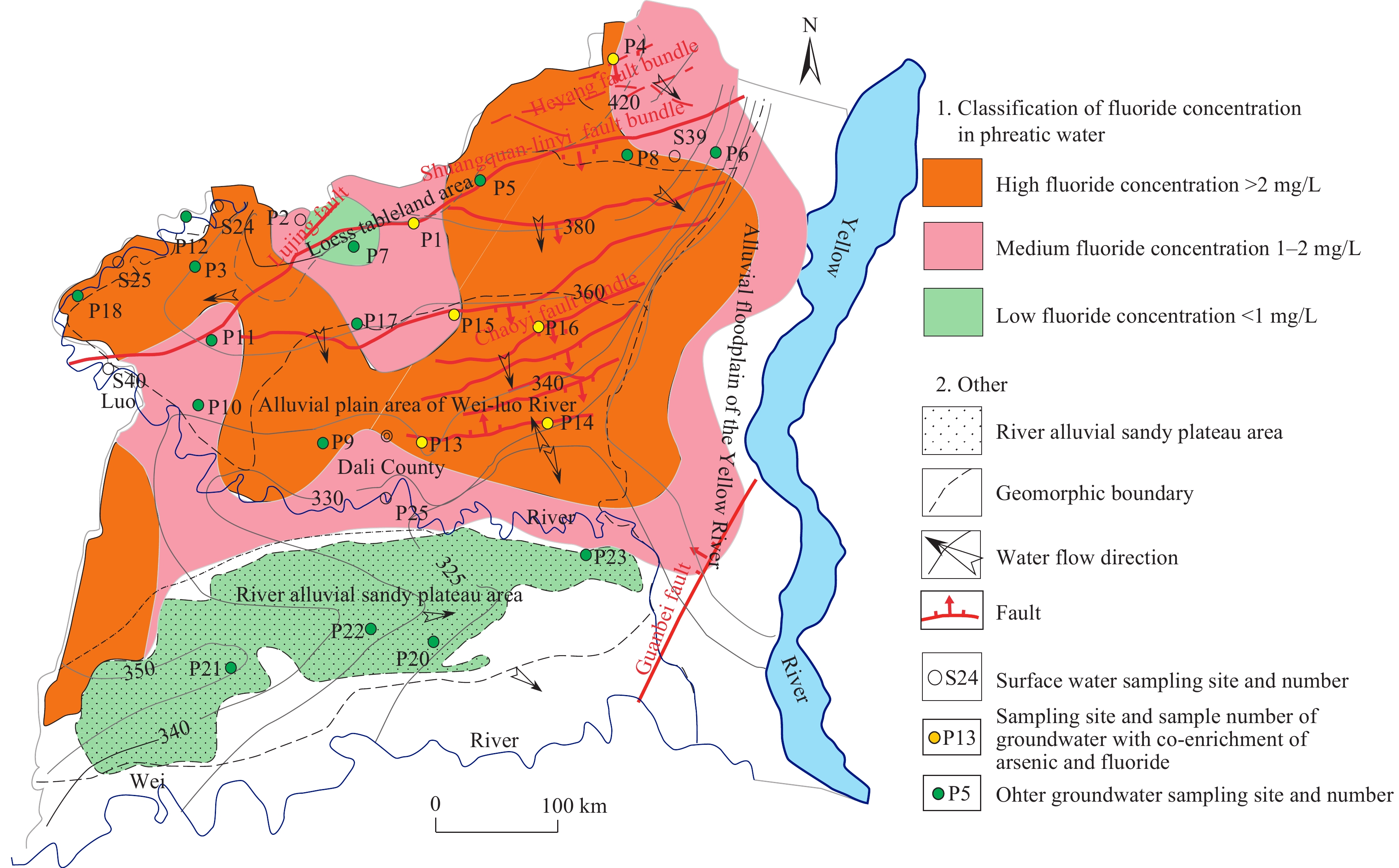

In this study, the hydrogeological conditions from the Beishan Mountain (also known as the Tielian Mountain) to the Weihe River were analyzed on a scale of a river basin (Fig. 1). The causes of contamination in the phreatic water and groundwater in Dali County and associated human health risks were investigated using samples collected primarily from Dali County, along with data principally from the Chengcheng County in the upper reaches. Among the samples, 23 groups of phreatic water samples (P1 to P23) were collected from private wells, monitoring wells, and boreholes, and 40 groups of confined water samples (labeled as C1 to C40) from private wells, monitoring wells, and boreholes. Besides, 17 groups of surface water samples (G24 to G40) were taken from boreholes in the low-lying land and rivers for comparison purposes. The sampling and sample preservation and handling were conducted following relevant national standards issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection of China (the present-day Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China) in 2009, along with relevant sampling rules. For instance, containers were rinsed three times using the water to be sampled prior to sampling. All samples were tested at the Northwest China Supervision and Inspection Center of Mineral Resources, Ministry of Natural Resources. The physicochemical indices analyzed included pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), total hardness (TH), major ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−, and CO32−), and fluoride content/concentrations in crops and water samples. The temperature, color, odor, taste, conductivity, Eh, and pH of the groundwater samples were measured on the sampling sites; Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ were analyzed using ICP spectroscopy, and Cl−, HCO3−, and CO32− were determined using ion chromatography. Additionally, SO42− and F− were analyzed using the specific gravity method and an ion-selective electrode method, respectively. The arsenic concentration was determined using atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS).

The hydrochemical components of the water samples were compared with GB/T 14848-2017 Standard for Groundwater Quality and relevant WHO guidelines to assess their suitability as drinking water. Based on the assessment results, F− and arsenic were selected for the non-carcinogenic health risk assessment, and the latter was also selected for the carcinogenic health risk assessment (Table 1). All the assessments were conducted using the US EPA’s risk assessment model and the parameter values suitable for the study area. Regarding exposure routes, this study considered water intake but ignored dermal contact due to the very low health risks of the latter (Chen J et al., 2017; Wu J et al., 2020).

| Parameter | Meaning | Kids | Adults | References |

| Ci | Fluoride or arsenic concentration in water | USEPA 2024; US EPA 2011; USEPA, 2005; USEPA, 1993 |

||

| IR | Daily intake of drinking water | 1.0 L/d | 0.6 L/d | |

| EF | Exposure frequency | 365 days | 365 days | |

| ED | Exposure duration | 12 years | 25 years | |

| BW | Body weight | 15.9 kg | 56.8 kg | |

| AT | Average time for non-carcinogenic effects | 4380 days | 9125 days | |

| RfDi | Non-carcinogenic reference dose of fluoride | 0.03 mg/(kg·d) | 0.06 mg/(kg·d) | |

| RfDj | Non-carcinogenic reference dose of arsenic | 0.0003 mg/(kg·d) | 0.0006 mg/(kg·d) | |

| SA | Surface area of groundwater in contact with skin | 8000 cm2 | 18000 cm2 | |

| PC | Skin permeability coefficient | 1.8×10−3 cm/h | ||

| ET | Average exposure frequency | 0.4167 h/d | 0.6333 h/d | |

| CF | Groundwater conversion factor | 10−3 mL/cm3 | ||

| HQi | Single non-carcinogenic risk index of the ith exposure route | HQi or THQ > 1 means high potential health risks, unacceptable to adults and kids. | ||

| THQi | Total non-carcinogenic risk index of all exposure routes for single contaminant i | |||

| CDi | Average daily exposure to non-carcinogenic heavy metals of the ith exposure route | |||

| ADDi | Average daily exposure to carcinogenic heavy metals of the ith exposure route | |||

| SFi | Slope coefficient of carcinogenic arsenic of the ith exposure route | The slope coefficients of exposure through the drinking and hand-mouth routes, the skin route, and the respiratory route are 1.5 kg·d/mg, 3.66 kg·d/mg, and 15.1 kg·d/mg, respectively. | ||

| CRi | Single carcinogenic risk index of the ith exposure route | CR or TCR values less than 10−6, between 10−6 and 10−4, and above 10−4 mean ignored, acceptable, and unacceptable carcinogenic risk levels, respectively, to the human body. | Rehman IU et al., 2018; Zeng SY et al., 2019 |

|

| TCR | Total carcinogenic risk index of groundwater | |||

US EPA’s risk assessment model was adopted, and the values of parameters were comprehensively considered based on the US EPA’s Exposure Factors Handbook (2011 Edition), the Exposure Factors Handbook of Chinese Population (Ministry of Environmental Protection of China, 2013), and related domestic studies (Zhou JM et al., 2019; Xiong J et al., 2020). Meanwhile, a comprehensive array of sources was referred to, including Equs. 1 and 2. Arsenic in water, exposed through water intake and skin contact, was meticulously accounted for in the assessment methodology (Zhou JM et al., 2019). The calculation equations for long-term average daily exposure to groundwater by two routes are as follows:

| ADDoral=(Ci×IR×EF×ED)/(BW×AT) | (1) |

| ADDdel=(Ci×SA×PC×ET×EF×ED×CF)/(BW×AT) | (2) |

| CRi=∑(ADDi×SFi) | (3) |

| CRi=∑[1−exp(−ADDi×SFi)] | (4) |

| TCR=∑CRi | (5) |

The model used for non-carcinogenic risk assessment of fluoride or arsenic through the oral or skin exposure routes is as follows:

| CDoral=(Ci×IR×EF×ED)/(BW×AT) | (6) |

| CDdel=(Ci×SA×PC×ET×EF×ED×CF)/(BW×AT) | (7) |

| HQi=CDi/RfD | (8) |

| THQ=∑HQi | (9) |

Dali County in Shaanxi Province, located in the eastern Guanzhong Plain and the Luohe River basin within the Guanzhong Basin, exhibits a well-developed river system composed of the Yellow, Luohe, and Weihe rivers (Fig. 1). With the Shayuan area in the south and Beishan Mountain in the north, this county is high in the northwest and low in the southeast and decline towards the Weihe River, forming a natural drainage pattern that influences the water flow across the country. With altitudes ranging from 330 to 500 m and a total area of 1766 km2, the Dali County contains landforms including a loess plateau, an alluvial plain of rivers, aeolian sand dunes, alluvial sands, and eroded structural depressions. The complex landforms suggest the nuanced interplay between geological processes shaping Dali County's terrains. Understanding the topographical characteristics is essential for the effective exploration of the hydrological dynamics and environmental processes in Dali County (Fig. 1).

Dali County has warm temperate, subhumid and semi-arid monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of 14.4°C, average annual precipitation of 514 mm, and average annual evaporation of 1200 mm. The groundwater in this county occurs primarily in Quaternary (Q4–Q1) porous phreatic aquifers, with Lower Pleistocene fluvial-lacustrine deposits identified as Qal+l. The Lower Pleistocene lacustrine basin in the county is located in the lower portion of the first-order loess plateau, with loess thicknesses exceeding 200 m and an elevation range of 540‒880 m, which is 40 m‒170 m higher than that of the alluvial plain. Only a minor amount of groundwater is exposed at the bottom of Jinshuigou in the north. The Lower Pleistocene fluvial-lacustrine deposits are composed of grayish-yellow clay with multiple fine sand layers. The Middle Pleistocene fluvial-lacustrine deposits (Q2al+l) underlie Q2eol and Q2al in the north of the Luohe River. They comprise clay interbedded with sands and gravels, with thicknesses ranging from 50 m to 100 m. The Middle Pleistocene aeolian deposits (Q2eol) are primarily distributed in the loess tableland and the fourth-order areas of the Weihe River. These deposits comprise brownish-yellow loess with multiple ancient soil layers, with thicknesses ranging between 90 m and 100 m. The Upper Pleistocene aeolian deposits (Q3eol) overlie the tableland area, with thicknesses varying between 10 and 15 m. The Pliocene alluvium (Q3al), being buried 50–60 m under the aeolian layer of the Weihe terrace, consists of silty clay, sandy soils, and gravels. The Holocene Q4 is distributed in the floodplain and terrace areas of the Yellow and Weihe rivers. It comprises silty soils, silty clay, sandy soils, and gravels, with thicknesses ranging between 10 m and 30 m (Liu RP et al., 2009).

Karst water in the north occurs primarily in the Lower Paleozoic Cambrian-Ordovician limestones. The Cambrian strata are dominated by marls and largely exhibit thinly laminated structures, serving as water-resisting layers. A thorough understanding of these geological and hydrogeological characteristics is essential for developing efficient strategies for sustainable water management and environmental conservation programs in Dali County (Wang D, 2016).

Gaining insights into the hydrochemical characteristics of Dali County, Shaanxi Province, is crucial to performing sustainable water management and mitigating potential health risks associated with water consumption.

The groundwater in Dali County features pH values varying from 7.15 to 8.64 (average: 8.00), suggesting neutral to weakly alkaline water generally. The phreatic water in the county exhibits TDS values [ρ(TDS)] ranging from 388 mg/L to 8360.26 mg/L, with an average of 2009.73 mg/L. Such water consists of fresh, brackish, and salt water with ρ(TDS) < 1000 mg/L, 1000 mg/L

| Indices | Confined water | Phreatic water | Surface water | Chinese guidelines | WHO guidelines | ||||||||

| Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | |||||

| TDS/(mg/L) | 680.43 | 5355.81 | 1716.05 | 388 | 8360.26 | 2265.82 | 711.62 | 38417.83 | 4713.84 | 1000 | 1000 | ||

| pH | 7.15 | 8.64 | 8.00 | 7.45 | 8.49 | 7.97 | 7.34 | 9.27 | 7.85 | 6.5–8.5 | 6.5–8.5 | ||

| Na+/(mg/L) | 28 | 1342 | 406.48 | 16.36 | 2096.1 | 520.88 | 87.7 | 11073.5 | 1201.57 | 200 | 200 | ||

| Ca2+/(mg/L) | 5.74 | 113 | 29.19 | 4.29 | 122 | 43.51 | 14.4 | 68.9 | 56.2 | / | / | ||

| Mg2+/(mg/L) | 15.3 | 219 | 62.83 | 11.2 | 402 | 96.87 | 27.3 | 1557 | 185.35 | / | / | ||

| Cl−/(mg/L) | 9.09 | 818.75 | 195.80 | 10.58 | 1400 | 288.89 | 66.17 | 9988 | 1100.41 | 250 | 250 | ||

| SO42−/(mg/L) | 85.85 | 2119.51 | 379.96 | 38.82 | 3639 | 630.04 | 155.3 | 14600 | 1527.69 | 250 | 250 | ||

| HCO3−/(mg/L) | 249.63 | 736.72 | 562.05 | 219.2 | 836 | 535.01 | 225.3 | 919 | 362.74 | / | / | ||

| CO32−/(mg/L) | 0 | 65.9 | 24.52 | 0 | 47.89 | 13.29 | 0 | 341.25 | 33.13 | / | / | ||

| F−/(mg/L) | 0.3 | 5.52 | 2.40 | 0.01 | 7 | 2.2 | 0.51 | 1.8 | 0.94 | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| As/(mg/L) | 0.00005 | 0.096 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.054 | 0.010 | − | − | − | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

Weakly alkaline fresh and brackish water (average pH value: 7.97) are concentrated in the recharge area of the loess plateau, with burial depths of phreatic aquifers ranging between 77 m and 140 m and dominant hydrochemical types identified as HCO3-Na and Cl·SO4-Na·Mg. In this study, 23 groups of phreatic water samples and 40 groups of confined water samples were collected, among which six groups of phreatic water samples and 12 groups of confined water samples displayed the co-enrichment of fluoride and arsenic, accounting for 26% and 30% of the corresponding samples, respectively. The co-enrichment of fluoride and arsenic is distributed in the loess plateau in eastern Dali County and the alluvial terraces of the Weihe River, where water levels range from 55 to 60 m, a small amount of salt water is discovered (Figs. 2 and 3), and complex and diverse hydrochemical types include Cl·SO4·HCO3-Na, Cl·HCO3-Na·Mg, HCO3-Na, Cl·SO4-Na, and SO4·HCO3−. Additionally, the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride is also observed in the groundwater recharge and drainage areas (from Gaoming Town to Chaoyi Town), spanning from the second- to fourth-order terraces of the Weihe River in eastern Dali County and around the structural depression in the second-order terraces of the Weihe River. These areas have burial depths varying from 55 m to 85 m, with primary hydrochemical types including HCO3-Na·Mg and Cl·SO4-Na.

Weakly alkaline fresh and brackish water (average pH value: 8.27) are concentrated in the recharge zone of the loess plateau, where the burial depths of the first and second confined aquifers range from 77 m to 140 m and from 257 m to 650 m, respectively, and hydrochemical types are dominated by HCO3-Na and Cl·SO4-Na·Mg. The co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride is identified in the first confined aquifer, with a burial depth of 120 m and high fluoride and arsenic concentrations varying from 2 mg/L to 2.16 mg/L and from 0.03 mg/L to 0.05 mg/L, respectively. The runoff areas consist of the third- and fourth-order alluvial terraces of the Weihe River, with confined water levels ranging from 116 m to 1096 m. These areas mainly host alkaline (average pH value: 7.87) and brackish water, with the presence of some salt and fresh water. The hydrochemical types become complex, including Cl·SO4·HCO3-Na, Cl·HCO3-Na·Mg, HCO3-Na, and HCO3-Na. The front of the third-order terrace of the Weihe River, exhibiting the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride in the first confined aquifer, has burial depths of less than 100 m. The alluvial plain in the second-order terrace of the Weihe River also demonstrates the enrichment of arsenic and fluoride. In this area, confined water has burial depths varying from 85.15 m to 623.40 m, dominated by weakly alkaline water (average pH value: 7.97), followed by fresh water, with the presence of a small amount of salt and fresh water (Figs. 4 and 5). The hydrochemical types in this area include HCO3·Cl-Na·Mg, HCO3-Na·Mg, HCO3-Na, and SO4·HCO3-Na. The co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride also occurs around the structural depression in the second-order area of the Weihe River, with burial depths ranging between 85.15 m and 395.593 m and primary hydrochemical types including HCO3-Na·Mg and Cl·SO4-Na. For both confined and phreatic water, the co-enrichment of fluoride and arsenic is primarily found in the recharge area of the loess area. The fourth- and third-order terraces of the Weihe River exhibit rapid runoff. In contrast, the first-order terrace and floodplain area show generally low fluoride and arsenic concentrations, which is related to surface water conservancy. However, both elements become enriched in the second-order terrace, highlighting the complex interplay between geological, hydrological, and anthropogenic factors in the dynamics of groundwater quality (Fig. 6).

The precondition for the formation of high fluoride water is fluoride sources, such as fluoride-rich rocks, sediments, and soils in the crust. Dali County is located along the eastern margin of the Guanzhong Basin, with the Beishan Mountain (also known as Tielian Mountain) with deep loess in the north, which provides rich fluoride for groundwater (Fig. 1). Numerous Paleozoic clastics are exposed in the Beishan Mountain, consisting primarily of limestones, marls, quartz sandstones, and shales. Of these, the marls, shales, and mudstones exhibit higher fluoride contents than the limestones and sandstones. The marls demonstrate a total fluoride content of 540 mg/kg, with a water-soluble fluoride content of 7.5 mg/kg, and the mudstones demonstrate total fluoride contents ranging from 600 mg/kg to 700 mg/kg, with a water-soluble fluoride content varying between 6.2 mg/kg and 12.5 mg/kg. The loess in the county, containing micas, hornblendes, tourmalines, and substantial clay substances, exhibits high fluoride contents ranging from 179 mg/kg to 490 mg/kg, with water-soluble fluoride contents reaching up to 4.9–34.0 mg/kg. Fluoride in rocks and loess migrates into the water under the action of hydration and leaching, leading to increased fluoride concentrations in groundwater. Fluoride-rich rocks, sediments, and soils provide abundant fluoride for groundwater (Liu RP et al., 2008, 2009). Loess and loam exhibit total fluoride contents of 619.20 mg/kg and 705.0 mg/kg and water-soluble fluoride contents of 7.00 mg/L and 6.6 mg/L, respectively, both of which exceed the average water-soluble fluoride content of environmental soils in China. The recharge and runoff areas contain abundant fluoride, marls, shales, and mudstones, which also serve as primary fluoride sources of groundwater. This further highlights the geological complexities, which influence the fluoride distribution in the hydrological system of the county (Zhu H et al., 2010).

The loess area in the Guanzhong Basin shows arsenic contents ranging from 12.7 to 1.72 mg/kg, with typical adsorbed arsenic and iron oxide-bound arsenic accounting for 37.76% and about 36.15%, respectively (Xue CZ et al., 1986). Significant correlations between arsenic and fluoride have been revealed in Chengcheng County, located to the north of Dali County, suggesting a common source. Furthermore, the arsenic concentrations (average: 0.003 mg/L) in groundwater in the upper reaches are significantly lower than the arsenic level for drinking water quality specified by WHO (0.01 mg/L), suggesting low proportions of arsenic and fluoride in volcanic rocks (Wang D, 2016). The medium-grained minerals of aquifers in the sewage systems across the Weihe River basin contain quartz, plagioclase, potash feldspar, calcite, dolomite, amphibole, and clay minerals like kaolinite, montmorillonite, chlorite, illite, ankerite, and hematite. Groundwater in the Weihe River basin generally manifests low arsenic concentrations, averaging 1.672 mg/L. High arsenic groundwater is distributed in Shicao Town, Dali County, with a maximum concentration of 24.94 mg/L (Gao YY, 2020). Mild arsenic contamination can be observed in groundwater in the Guanzhong Plain. Meanwhile, severe arsenic contamination occurs in eastern Huxian County on both sides of the Fenghe River, the western part of the center of Xi'an City, and some areas of Dali County. Figs. 1 and 4 indicate that partial arsenic in groundwater originates from arsenic-rich minerals like arsenopyrite. Subjected to fault activity, arsenic-rich deep confined water rises along faults or ground fissures to recharge phreatic water, leading to excess arsenic in phreatic water. The high-amplitude arsenic and fluoride anomalies in groundwater in Dali County stem principally from the impacts of fault structures. Fig. 4 illustrates that faults pass through areas with anomalously high arsenic and fluoride concentrations. Contributing to groundwater motion along the fault zone, deep groundwater with high arsenic and fluoride concentrations remains in a relatively stable small range with continuous groundwater exploitation (Gao Y et al., 2020). However, most areas with the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride in the Guanzhong Basin are located in Xi'an City and Dali County, further demonstrating that fault structures are primary factors governing the element enrichment of groundwater with high background values in the Guanzhong Basin.

Hydrogeological conditions prove crucial to the migration and enrichment of fluoride and arsenic in groundwater. From the perspective of a river basin, the groundwater from the Beishan Mountain to the Weihe River in Chengcheng County within the Dayu River basin exhibits fluoride concentrations mostly exceeding 1.0 mg/L, averaging 1.15 mg/L, whereas the groundwater in Dali County manifests an average fluoride concentration of 2.30 mg/L. Except for the low mountain in the groundwater recharge and runoff areas and the piedmont alluvial fan area, areas in the Weihe River basin exhibit groundwater with over-limit fluoride concentrations. Along the groundwater flow direction, the fluoride concentration increases from north to south, especially from southeastern Chengcheng County to the terraces of the Weihe River in Dali County. Areas with over-limit fluoride concentrations are extensively distributed, with fluoride concentrations 2 times to 10.8 times the upper limit for drinking water safety. The areas, where groundwater with over-limit fluoride concentrations (maximum: 2.69 mg/L) occur in Carboniferous-Triassic clastics, are primarily distributed in the second-order loess plateau area, that is, the Xishe Township-Wangzhuang Town-Luojiawa Town area in the north and the Chengguan Town in the south. Karst water in Cambrian-Ordovician carbonate rocks exhibits relatively low fluoride concentrations, typically ranging from 0.95 mg/L to 1.2 mg/L. The groundwater in Chengcheng County and Dali County exhibit average arsenic concentrations of 0.003 mg/L and 0.01 mg/L (maximum: 0.096 mg/L), respectively. These findings underscore the significant fluoride enrichment in groundwater across Dali County. Local areas in this county exhibit elevated arsenic concentrations, highlighting that comprehensive hydrogeological assessments are crucial to effective water resource management and public health (Wang D, 2016).

Hydrodynamic conditions govern the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater (Figs. 1‒5). For the water flow system in Dali County, the loess tableland is identified as a recharge area of arsenic and fluoride, and the groundwater samples with high arsenic and fluoride concentrations are primarily collected in the drainage area. As water flows from the recharge area to the transition and evaporation areas, the lithology of aquifers shifts from loess to gravels interbedded with clayey silts and loams, with the terrain becoming gradually gentle. During this process, groundwater manifests a decreasing hydraulic gradient, slow runoff, and shallow water tables. These characteristics, as well as local structural depressions, establish evaporation as the primary way of groundwater discharge. Besides, the large deposition thicknesses of loess, low permeability coefficients, weak hydrodynamic conditions, and extremely slow water cycle alternating can be observed. Sufficient water-rock interactions render fluoride ions in soils and rocks to enter groundwater, and the overall alkaline water in the area contributes to ion enrichment. Additionally, evaporation emerges as the primary way of groundwater discharge due to the shallow water tables and intense evaporation. Consequently, most areas around Dali County and the northern Weihe River exhibit elevated arsenic and fluoride concentrations, leading to enriched arsenic and fluoride in groundwater. These findings underscore the intricate interplay between hydrodynamic processes and geological factors influencing groundwater quality. Therefore, comprehensive hydrogeological assessments are significant for effective resource management and environmental protection.

The study of hydrogeochemistry relies on the proportional coefficients between groundwater components [Institute of Geology and Geophysics (IGG), 2020]. The γ(Ca2+)/γ(Cl-) ratio can be used to describe the hydrodynamic characteristics of groundwater. A higher γ(Ca2+)/γ(Cl-) ratio suggests more favorable hydrodynamic conditions. The γ(SO42-)/γ(Cl-) ratio indicates the redox conditions in groundwater, with high values corresponding to stronger oxidation (Sun Y et al., 2022). The results of this study indicate that the confined water in Dali County exhibits γ(Ca2+)/γ(Cl-) ratios ranging from 0.0035 to 4.78 (average: 0.348), which decrease from the recharge area (average: 0.715) to the transition area (average: 0.397) and then to the evaporation area (average: 0.187). In contrast, the phreatic water demonstrates γ(Ca2+)/γ(Cl-) ratios varying from 0.0038 to 6.144 (average: 0.752), which decrease from the recharge area (average: 0.190) to the transition area (average: 0.181) and then to the evaporation area (average: 0.073). The confined water displays γ(SO42-)/γ(Cl-) ratios ranging from 0.061 to 1.506 (average: 0.581), which increase from the recharge area (average: 0.178) to the transition area (average: 0.533) and then to the evaporation area (average: 0.909). In contrast, the phreatic water exhibits γ(SO42-)/γ(Cl-) ratios ranging from 0.087 to 0.955 (average: 0.505), which increase from the recharge area (average: 0.357) to the transition area (average: 0.371) and then to the evaporation area (average: 0.716). The phreatic water in the recharge, transition, and evaporation areas demonstrate average TDS values of 2624.61 mg/L, 3288.12 mg/L, and 4812.00 mg/L respectively, with groundwater changing from brackish water to salt water. The confined water in these three areas shows average TDS values of 1237.82 mg/L, 1387.58 mg/L, and 1396.53 mg/L, respectively, with the burial depths of the first confined aquifer varying between 77 m and 140 m. This further indicates that groundwater has been recharged by overflow. Evaporation intensifies along the groundwater flow path from the recharge area to the evaporation area.

This study revealed the hydrogeochemical characteristics in Dali County using various analytical approaches, shedding light on the intricate mechanisms governing groundwater geochemistry. Furthermore, the sources of fluoride and arsenic in the water samples were analyzed using Gibbs diagrams. Fig. 7 shows that all the water samples fell within the rock and evaporation dominance zones, suggesting that the groundwater and surface-water geochemistry of Dali County is governed by rock weathering, water-rock interactions, and evaporation. High and low fluoride water exhibited quite different mechanisms behind quality evolution, indicating that natural processes dominate the water quality evolution in Dali County. Groundwater is distributed near rock weathering areas, suggesting high arsenic and fluoride concentrations in groundwater in Dali County.

High fluoride water was formed in alkaline environments (high pH values) with high Na+ and HCO3− concentrations and low Ca2+ concentrations in the study area (Liu RP et al., 2021). High arsenic groundwater occurs primarily in alkaline reducing environments with high soluble salt concentrations in aqueous media (> 200 mg/100 g of dry soil). The reductive dissolution of iron and manganese oxides and the competitive adsorption of Na+ and HCO3− both lead to high arsenic concentrations in unconfined and confined aquifers (Dong SG et al., 2022). The following table shows that Na+ and HCO3− in groundwater contribute to the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride. The areas with the co-enrichment, primarily located in Xi'an City and Dali County, underscore the significant impacts of fault systems on the geochemical composition of groundwater (Table 2).

Another primary source of arsenic is human activities, including the discharge of arsenic-bearing wastewater from facilities, the application of arsenic-bearing pesticides or insecticides, and irrigation with treated wastewater (Gao Y, Qian H, Wang H, 2019). Dali County is an agricultural producer, with two agricultural irrigation areas to the north of the Luohe River primarily distributed in the west. This is consistent with the high arsenic concentrations in groundwater. However, this conclusion is yet to be further verified in subsequent research.

The carcinogenic risk assessment of arsenic (Table 4) and the non-carcinogenic risk assessment of arsenic and fluoride (Table 5) in groundwater were performed in this study. The risk indices and their characteristic statistics were obtained according to different exposure routes. Tables 3 and 4 show that compared to adults, kids face higher carcinogenic risks caused by arsenic and non-carcinogenic risks arising from arsenic and fluoride in groundwater, whether through oral intake or skin contact. In terms of exposure routes, oral intake of arsenic can cause about several hundred times higher carcinogenic risks than skin contact, indicating that oral intake is the dominant route causing health risks of arsenic and fluoride. Regarding groundwater types, confined water can cause higher health risks than phreatic water. As calculated based on the average and maximum values, the carcinogenic risk index of arsenic exceeds 10−4, while the non-carcinogenic risk indices of arsenic and fluoride exceed 1. These values are unacceptable to both adults and kids.

| ID | Geomorphic type | Aquifer | TDS | pH | As | F | Hydrochemical type |

| P1 | Loess | Phreatic water | 3845.12 | 8.30 | 0.013 | 1.44 | Cl·SO4-Na·Mg |

| P4 | Loess | Phreatic water | 1872.85 | 8.32 | 0.050 | 2.16 | SO4·HCO3-Na |

| P13 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 7288.95 | 7.74 | 0.030 | 2.16 | Cl·SO4-Na·Mg |

| P14 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 1177.00 | 8.36 | 0.013 | 6.16 | HCO3-Na |

| P15 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 2335.04 | 8.25 | 0.014 | 3.90 | HCO3·Cl-Na |

| P16 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 1191.72 | 8.23 | 0.054 | 7.00 | HCO3-Na |

| C15 | Loess | Confined water | 1287.51 | 8.30 | 0.02 | 2.00 | HCO3-Na |

| C16 | Loess | Confined water | 1249.26 | 8.25 | 0.05 | 2.16 | HCO3-Na |

| C17 | Loess | Confined water | 1200.01 | 8.02 | 0.02 | 2.66 | HCO3-Na |

| C19 | Loess | Confined water | 1406.90 | 8.30 | 0.03 | 2.00 | SO4·HCO3-Na |

| C20 | Loess | Confined water | 1155.19 | 8.26 | 0.02 | 2.10 | HCO3-Na |

| C21 | Loess | Confined water | 1123.55 | 8.28 | 0.03 | 2.55 | HCO3-Na |

| C22 | River terrace | Confined water | 1308.49 | 8.22 | 0.03 | 2.76 | SO4·HCO3-Na |

| C23 | River terrace | Confined water | 1464.45 | 8.25 | 0.03 | 2.74 | HCO3-Na |

| C24 | River terrace | Confined water | 1186.45 | 8.24 | 0.02 | 2.24 | HCO3-Na·Mg |

| C25 | River terrace | Confined water | 1396.53 | 8.32 | 0.06 | 5.52 | HCO3-Na |

| C35 | River terrace | Confined water | 1405.31 | 8.04 | 0.02 | 4.16 | Cl·HCO3-Na |

| C38 | River terrace | Confined water | 2819.16 | 8.29 | 0.02 | 3.60 | Cl·SO4-Na |

| Groundwater type | Characteristic value | CRoral | CRder | TCR | |||||

| Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | ||||

| Confined water | Minimum | 0.0000028 | 0.0000013 | 0.00000001 | 0.000000007 | 0.0000028 | 0.0000013 | ||

| Maximum | 0.00542 | 0.00253 | 0.000013 | 0.0000127 | 0.00543 | 0.00254 | |||

| Average | 0.00073 | 0.00034 | 0.0000018 | 0.0000017 | 0.00073 | 0.00034 | |||

| Phreatic water | Minimum | 0.000028 | 0.000013 | 0.000000069 | 0.000000066 | 0.000028 | 0.000013 | ||

| Maximum | 0.003050 | 0.00143 | 0.0000075 | 0.0000071 | 0.00306 | 0.00143 | |||

| Average | 0.000561 | 0.00026 | 0.0000014 | 0.0000013 | 0.00056 | 0.00026 | |||

| Groundwater type | Characteristic value | HQoral | HQder | THQ | |||||

| Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | ||||

| Confined water | Minimum of fluoride | 0.189 | 0.088 | 0.00019 | 0.00018 | 0.19 | 0.09 | ||

| Maximum of fluoride | 3.472 | 1.620 | 0.0035 | 0.0033 | 3.48 | 1.62 | |||

| Average of fluoride | 1.510 | 0.705 | 0.0015 | 0.0014 | 1.51 | 0.71 | |||

| Phreatic water | Minimum of fluoride | 0.0063 | 0.0029 | 0.000006 | 0.000006 | 0.0063 | 0.0029 | ||

| Maximum of fluoride | 4.40 | 2.05 | 0.0044 | 0.0042 | 4.41 | 2.06 | |||

| Average of fluoride | 1.38 | 0.65 | 0.0014 | 0.0013 | 1.38 | 0.65 | |||

| Confined water | Minimum of arsenic | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.0063 | 0.0029 | ||

| Maximum of arsenic | 12.075 | 5.634 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 12.09 | 5.65 | |||

| Average of arsenic | 1.621 | 0.756 | 0.0016 | 0.0016 | 1.62 | 0.76 | |||

| Phreatic water | Minimum of arsenic | 0.063 | 0.029 | 0.000063 | 0.00006 | 0.063 | 0.029 | ||

| Maximum of arsenic | 6.792 | 3.169 | 0.0068 | 0.0065 | 6.80 | 3.18 | |||

| Average of arsenic | 1.247 | 0.582 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 1.25 | 0.58 | |||

This study aims to explore the causes of element occurrence in groundwater in endemic areas associated with drinking water. Based on 80 sets of field data and a systematic basin view, this study innovatively investigates the occurrence mechanisms and carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic human health risks of high fluoride and arsenic concentrations in groundwater in the loess area of Dali County, Shaanxi Province, China. The findings lead to the following conclusions.

(i) The co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater in Dali County is primarily caused by natural and anthropogenic factors. The loess area, rich in arsenic and fluoride, is characterized by gentle terrain, weak hydrodynamic conditions, and extremely slow water cycle alternating. Complete water-rock interactions and strong evaporation accelerate ion enrichment in the whole county, with Na+ and HCO3− in groundwater serving as significant hydrogeochemical factors facilitating the co-enrichment of arsenic and fluoride. The well-developed structural faults act as a primary factor controlling the element enrichment in groundwater with high background values in the Guanzhong Basin. Additionally, irrigation after pesticide application and fertilization in agriculture-oriented Dali County might be another anthropogenic factor.

(ii) The groundwater with fluoride and arsenic concentrations exceeding the limits specified in the national hygiene standard for drinking water is still the main water source for local residents. Since long-term intake of such groundwater is prone to induce endemic diseases, it is inadvisable to use such groundwater for domestic water needs. The local governments are recommended to establish water sources in Shayuan and karst areas in the northwest to improve the water supply.

(iii) The assessment results of human health risks posed by arsenic and fluoride in groundwater demonstrate that groundwater with high arsenic and fluoride concentrations is unacceptable to the human body, especially for kids. It is recommended that low-risk areas such as Shayuan serve as sources of water supply for local residents. Notably, it is necessary to protect kids’ health and improve people’s drinking habits.

Rui-ping Liu and Jian-Gang Jiao wrote the manuscript. Others helped Rui-ping Liu conceive the original idea of this study. El-Wardany RM polished this manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This study was funded by the ministry-province cooperation-based pilot project entitled A Technological System for Ecological Remediation Evaluation of Open-Pit Mines initiated by the Ministry of Natural Resources in 2023 (2023-03), survey projects of the Land and Resources Investigation Program ([2023]06-03-04, 1212010634713), and a key R&D projects of Shaanxi Province in 2023 (2023-ZDLSF-63). The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the Experiment and Testing Laboratory of Xi’an Center, China Geological Survey for the statistical data analyses.

|

Berger T, Mathurin FA, Drake H, Åström ME. 2016. Fluoride abundance and controls in fresh groundwater in Quaternary deposits and bedrock fractures in an area with fluorine-rich granitoid rocks. Science of the Total Environment, 569–570, 948–960. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.002.

|

|

Chen HH, Chen HW, He JT. 2006. Health-based risk assessment of contaminated sites: Principles and methods. Earth Science Frontiers, 13(1), 216–223 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.1016/S1872-2040(06)60041-8.

|

|

Chen J, Qian H, Wu H. 2017. Health risk assessment of water environment in drinking groundwater well fields based on triangular fuzzy number theory. South - to - North Water Transfers and Water Science and Technology, 15(03), 80–85 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.13476/j.cnki.nsbdqk.2017.03.014.

|

|

Chen J, Qian H, Wu H. Gao Y, Li X. 2017. Assessment of arsenic and fluoride pollution in groundwater in Dawukou area, Northwest China, and the associated health risk for inhabitants. Environmental Earth Sciences, 76, 314. doi: 10.1007/s12665-017-6629-2.

|

|

Dong SG, Liu BW, Chen Y, Ma MY, Liu XB, Wang C. 2022. Hydro-geochemical control of high arsenic and fluoride groundwater in arid and semi-arid areas: A case study of Tumochuan Plain, China. Chemosphere, 301, 134657. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134657.

|

|

Deng AQ, Dong ZM, Gao Q, Hu JY. 2017. Health risk assessment of arsenic in groundwater across China. China Environmental Science, 37(9), 3556–3565.

|

|

Estrada-Capetillo BL, Ortiz-Perez MD, Salgado-Bustamante M, Calderón-Aranda E, Rodríguez-Pinala CJ, Reynaga-Hernández E, Corral-Fernandez NE, González-Amaro R, Portales-Perez DP. 2014. Arsenic and fluoride co-exposure affects the expression of apoptotic and inflammatory genes and proteins in mononuclear cells from children. Mutation Research, 731, 27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2014.01.006.

|

|

Gao YY, Qian H, Wang HK, Chen J, Ren WH, Yang FX. 2020. Assessment of background levels and pollution sources for arsenic and fluoride in the phreatic and confined groundwater of Xi’an city, Shaanxi, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27, 34702–34714. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06791-7.

|

|

Gao YY. 2020. Spatio-temporal evolution of hydrochemical components and human health risk assessment of groundwater in Guanzhong Plain. A dissertation submitted for the degree of doctor of Chang’an University. 1‒196 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.26976/d.cnki.gchau.2020.000029.

|

|

Guo HM, Ni P, Jia YF. 2014. Types, chemical characteristics, and genesis of geogenic high-arsenic groundwater in the world. Earth Science Frontiers, 21(4), 1‒12. doi: 10.13745/j.esf.2014.04.001.

|

|

He XD, Li PY, Ji YJ, Wang YH, Su ZM, Elumalai V. 2020. Groundwater arsenic and fluoride and associated arsenicosis and fluorosis in China: Occurrence, distribution and management. Exposure and Health 12, 355–368. doi: 10.1007/s12403-020-00347-8.

|

|

Hossain M, Patra PK. 2020. Contamination zoning and health risk assessment of trace elements in groundwater through geostatistical modelling. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 189, 110038. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110038.

|

|

Institute of Geology and Geophysics, China Academy of Sciences. 2020. Global Distribution and Hazards of High Arsenic Groundwater (in Chinese). http://www.igg.cas.cn/xwzx/cutting_edge/202008/t20200824_5671956.html.

|

|

IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety). 2001. Arsenic and arsenic compounds. http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc224.html.

|

|

Liu RP. 2009. Study on transference and transform simulation of fluoride in groundwater and relation between fluoride and human body health in Dali Region, Guanzhong Basin. Xi’an, Chang’an University, Master’ thesis, 1‒65. (in Chinese with English abstract).

|

|

Liu RP, Zhu H, Yang BC, Zhao AN. 2008. Occurrence pattern and hydrochemistry cause of the shallow groundwater fluoride in the Dali County, Shaanxi Province. Northwestern Geology, 41(4), 134–141 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6248.2008.04.010.

|

|

Liu RP, Zhu H, Liu F, Dong Y, El-Wardany RM. 2021. Current situation and human health risk assessment of fluoride enrichment in groundwater in the Loess Plateau: A case study of Dali County, Shaanxi Province, China. China Geology, 3(3), 487–497. doi: 10.31035/cg2021051.

|

|

Li YM. 2021. Distribution and harm of high arsenic groundwater in the world (in Chinese), http://www.igg.cas.cn/xwzx/cutting_edge/202008/t20200824_5671956.html.

|

|

Ministry of Environment Protection. 2013. Exposure factors hand book of Chinese population. adult volume. Beijing, China Environmental Science Press, 1–265.

|

|

Rehman IU, Ishag M, Ali L. 2018. Enrichment, spatial distribution of potential ecological and human health risk assessment via toxic metals in soil and surface water ingestion in the vicinity of Sewakht mines, district Chitral, Northern Pakistan. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 154: 127‒136. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.02.033.

|

|

Ren Y, Cao WG, Pan D. 2021. Evolution characteristics and change mechanism of arsenic and fluorine in shallow groundwater from a typical irrigation area in the lower reaches of the Yellow River (Henan) in 2010‒2020. Rock and Mineral Analysis, 40 (6), 846–859 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.15898/j.cnki.11-2131/td.202110090143.

|

|

Su X, Wang H, Zhang Y. 2013. Health risk assessment of nitrate contamination in groundwater: A case study of an agricultural area in northeast China. Water Resources Management, 27(8), 3025‒3034. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07075-w.

|

|

Sun Y, Zhou JL, Yang FY. 2022. Distribution and co-enrichment genesis of arsenic, fluorine, and iodine in groundwater of the oasis belt in the southern margin of Tarim Basin. Earth Science Frontiers, 29 (3), 099–114. doi: 10.13745/j.esf.sf.2022.1.33.

|

|

US EPA. 2011. Exposure Factors Handbook (2011 Edition). Washington: U. S. Environmental Protection Agency.

|

|

USEPA.1993. Reference Dose (RfD): Description and Use in Health Risk Assessments. Background Document 1A. https://www.epa.gov/iris/reference-dose-rfd-description-and-use-health-risk-assessments#main-content. March, 1993.

|

|

USEPA. 2005. Guidelines for carcinogen risk assessment. Risk assessment forum. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. EPA/630/P-03/001F. March, 2005.

|

|

USEPA. 2024. Regional Screening Levels (RSLs) - Generic Tables. https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables. May 2024.

|

|

Wang D. 2016. Spatial distribution and factors of fluoride groundwater in Chengcheng County, Shaanxi Province, Jilin University, Changchun, Master’s thesis, 1‒86 (in Chinese with English abstract).

|

|

Wang YY, Cao WG, Pan D, Wang S, Ren Y, Li ZY. 2022. Distribution and origin of high arsenic and fluoride in groundwater of the north Henan Plain. Rock and Mineral Analysis, 41(6), 1095–1109 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.15898/j.cnki.11-2131/td.202110090141.

|

|

Wang Z, Chai L, Wang YY, Yang Z, Wang H, Wu X. 2011. Potential health risk of arsenic and cadmium in groundwater near Xiangjiang River, China: A case study for risk assessment and management of toxic substances. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 175(1–4), 167–173. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1503-7.

|

|

Wu J, Li J, Teng Y, Chen H, Wang Y. 2020. A partition computing-based positive matrix factorization (PC-PMF) approach for the source apportionment of agricultural soil heavy metal contents and associated health risks. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 121766 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121766.

|

|

WHO (World Health Organization). 2011. Arsenic in drinking-water: Background document for development of WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality. Switzerland, WHO Press.

|

|

Wang YX, Li JX, Ma T. 2021. Genesis of geogenic contaminated groundwater: As, F and I. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 51(24), 2895–2933. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2020.1807452.

|

|

Xiong J, Han ZW, Wu P, Zeng, X, Luo G, Yang W. 2020. Spatial distribution characteristics, contamination evaluation and health risk assessment of arsenic and antimony in soil around an antimony smelter of Dushan County. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae, 40(2), 655–664. doi: 10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2019.0387.

|

|

Xue CZ, Xiao L, Wu QF, Li DY, Wang KX, Li HG, Wang R. 1986. Studies of Background Values of Ten Chemical Elements in Major Agricultural Soils in Snaanxi Province, 14(3), 1–24.

|

|

Yu Q, Zhang Y, Dong T, Wu GW, Li P. 2023. Effect of Surface Water-Groundwater Interaction on Arsenic Transport in Shallow Groundwater of Jianghan Plain. Earth Science. 48(09), 3420‒3431 (in Chinese with English abstract). https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/42.1874.P.20220506.1102.010.html.

|

|

Zango MS, Sunkari ED, Abu M. 2019. Hydrogeochemical controls and human health risk assessment of groundwater fluoride and boron in the semi-arid North East region of Ghana. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 207, 106363. doi: 10.1016/j.gexplo.2019.106363.

|

|

Zhang ZJ, Fei NH, Chen ZY. 2009. Investigation and evaluation of sustainable utilization of groundwater in North China Plain. Beijing, Geological Publishing House, 35‒40 (in Chinese).

|

|

Zhou YZ, Guo HM, Zhang Z. 2018. Characteristics and implication of stable carbon isotope in high arsenic groundwater systems in the northwest Hetao Basin, Inner Mongolia, China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 163, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2018.05.018.

|

|

Zeng SY, Ma J, Yang YJ. 2019. Spatial assessment of farmland soil pollution and its potential human health risks in China. Science of the Total Environment, 687, 642–653. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.291.

|

|

Zhou JM, Jiang ZC, Xu GL, Qin XQ. Huang QB, Zhang LK. 2019. Distribution and health risk assessment of metals in groundwater around iron mine. China Environmental Science, 39(5), 1934–1944. doi: 10.19674/j.cnki.issn1000-6923.2019.0230.

|

|

Zhu H, Yang BC, Zhao AN, Ke HL, Qiao G. 2010. The formation regularity of high-fluorine groundwater in Dali County, Shaanxi Province. Geology in China, 37(03), 672–676 (in Chinese with English abstract). doi: 10.1016/S1876-3804(11)60004-9.

|

| Parameter | Meaning | Kids | Adults | References |

| Ci | Fluoride or arsenic concentration in water | USEPA 2024; US EPA 2011; USEPA, 2005; USEPA, 1993 |

||

| IR | Daily intake of drinking water | 1.0 L/d | 0.6 L/d | |

| EF | Exposure frequency | 365 days | 365 days | |

| ED | Exposure duration | 12 years | 25 years | |

| BW | Body weight | 15.9 kg | 56.8 kg | |

| AT | Average time for non-carcinogenic effects | 4380 days | 9125 days | |

| RfDi | Non-carcinogenic reference dose of fluoride | 0.03 mg/(kg·d) | 0.06 mg/(kg·d) | |

| RfDj | Non-carcinogenic reference dose of arsenic | 0.0003 mg/(kg·d) | 0.0006 mg/(kg·d) | |

| SA | Surface area of groundwater in contact with skin | 8000 cm2 | 18000 cm2 | |

| PC | Skin permeability coefficient | 1.8×10−3 cm/h | ||

| ET | Average exposure frequency | 0.4167 h/d | 0.6333 h/d | |

| CF | Groundwater conversion factor | 10−3 mL/cm3 | ||

| HQi | Single non-carcinogenic risk index of the ith exposure route | HQi or THQ > 1 means high potential health risks, unacceptable to adults and kids. | ||

| THQi | Total non-carcinogenic risk index of all exposure routes for single contaminant i | |||

| CDi | Average daily exposure to non-carcinogenic heavy metals of the ith exposure route | |||

| ADDi | Average daily exposure to carcinogenic heavy metals of the ith exposure route | |||

| SFi | Slope coefficient of carcinogenic arsenic of the ith exposure route | The slope coefficients of exposure through the drinking and hand-mouth routes, the skin route, and the respiratory route are 1.5 kg·d/mg, 3.66 kg·d/mg, and 15.1 kg·d/mg, respectively. | ||

| CRi | Single carcinogenic risk index of the ith exposure route | CR or TCR values less than 10−6, between 10−6 and 10−4, and above 10−4 mean ignored, acceptable, and unacceptable carcinogenic risk levels, respectively, to the human body. | Rehman IU et al., 2018; Zeng SY et al., 2019 |

|

| TCR | Total carcinogenic risk index of groundwater | |||

| Indices | Confined water | Phreatic water | Surface water | Chinese guidelines | WHO guidelines | ||||||||

| Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | Mean | |||||

| TDS/(mg/L) | 680.43 | 5355.81 | 1716.05 | 388 | 8360.26 | 2265.82 | 711.62 | 38417.83 | 4713.84 | 1000 | 1000 | ||

| pH | 7.15 | 8.64 | 8.00 | 7.45 | 8.49 | 7.97 | 7.34 | 9.27 | 7.85 | 6.5–8.5 | 6.5–8.5 | ||

| Na+/(mg/L) | 28 | 1342 | 406.48 | 16.36 | 2096.1 | 520.88 | 87.7 | 11073.5 | 1201.57 | 200 | 200 | ||

| Ca2+/(mg/L) | 5.74 | 113 | 29.19 | 4.29 | 122 | 43.51 | 14.4 | 68.9 | 56.2 | / | / | ||

| Mg2+/(mg/L) | 15.3 | 219 | 62.83 | 11.2 | 402 | 96.87 | 27.3 | 1557 | 185.35 | / | / | ||

| Cl−/(mg/L) | 9.09 | 818.75 | 195.80 | 10.58 | 1400 | 288.89 | 66.17 | 9988 | 1100.41 | 250 | 250 | ||

| SO42−/(mg/L) | 85.85 | 2119.51 | 379.96 | 38.82 | 3639 | 630.04 | 155.3 | 14600 | 1527.69 | 250 | 250 | ||

| HCO3−/(mg/L) | 249.63 | 736.72 | 562.05 | 219.2 | 836 | 535.01 | 225.3 | 919 | 362.74 | / | / | ||

| CO32−/(mg/L) | 0 | 65.9 | 24.52 | 0 | 47.89 | 13.29 | 0 | 341.25 | 33.13 | / | / | ||

| F−/(mg/L) | 0.3 | 5.52 | 2.40 | 0.01 | 7 | 2.2 | 0.51 | 1.8 | 0.94 | 1 | 1.5 | ||

| As/(mg/L) | 0.00005 | 0.096 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.054 | 0.010 | − | − | − | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| ID | Geomorphic type | Aquifer | TDS | pH | As | F | Hydrochemical type |

| P1 | Loess | Phreatic water | 3845.12 | 8.30 | 0.013 | 1.44 | Cl·SO4-Na·Mg |

| P4 | Loess | Phreatic water | 1872.85 | 8.32 | 0.050 | 2.16 | SO4·HCO3-Na |

| P13 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 7288.95 | 7.74 | 0.030 | 2.16 | Cl·SO4-Na·Mg |

| P14 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 1177.00 | 8.36 | 0.013 | 6.16 | HCO3-Na |

| P15 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 2335.04 | 8.25 | 0.014 | 3.90 | HCO3·Cl-Na |

| P16 | River terrace | Phreatic water | 1191.72 | 8.23 | 0.054 | 7.00 | HCO3-Na |

| C15 | Loess | Confined water | 1287.51 | 8.30 | 0.02 | 2.00 | HCO3-Na |

| C16 | Loess | Confined water | 1249.26 | 8.25 | 0.05 | 2.16 | HCO3-Na |

| C17 | Loess | Confined water | 1200.01 | 8.02 | 0.02 | 2.66 | HCO3-Na |

| C19 | Loess | Confined water | 1406.90 | 8.30 | 0.03 | 2.00 | SO4·HCO3-Na |

| C20 | Loess | Confined water | 1155.19 | 8.26 | 0.02 | 2.10 | HCO3-Na |

| C21 | Loess | Confined water | 1123.55 | 8.28 | 0.03 | 2.55 | HCO3-Na |

| C22 | River terrace | Confined water | 1308.49 | 8.22 | 0.03 | 2.76 | SO4·HCO3-Na |

| C23 | River terrace | Confined water | 1464.45 | 8.25 | 0.03 | 2.74 | HCO3-Na |

| C24 | River terrace | Confined water | 1186.45 | 8.24 | 0.02 | 2.24 | HCO3-Na·Mg |

| C25 | River terrace | Confined water | 1396.53 | 8.32 | 0.06 | 5.52 | HCO3-Na |

| C35 | River terrace | Confined water | 1405.31 | 8.04 | 0.02 | 4.16 | Cl·HCO3-Na |

| C38 | River terrace | Confined water | 2819.16 | 8.29 | 0.02 | 3.60 | Cl·SO4-Na |

| Groundwater type | Characteristic value | CRoral | CRder | TCR | |||||

| Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | ||||

| Confined water | Minimum | 0.0000028 | 0.0000013 | 0.00000001 | 0.000000007 | 0.0000028 | 0.0000013 | ||

| Maximum | 0.00542 | 0.00253 | 0.000013 | 0.0000127 | 0.00543 | 0.00254 | |||

| Average | 0.00073 | 0.00034 | 0.0000018 | 0.0000017 | 0.00073 | 0.00034 | |||

| Phreatic water | Minimum | 0.000028 | 0.000013 | 0.000000069 | 0.000000066 | 0.000028 | 0.000013 | ||

| Maximum | 0.003050 | 0.00143 | 0.0000075 | 0.0000071 | 0.00306 | 0.00143 | |||

| Average | 0.000561 | 0.00026 | 0.0000014 | 0.0000013 | 0.00056 | 0.00026 | |||

| Groundwater type | Characteristic value | HQoral | HQder | THQ | |||||

| Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | Kids | Adults | ||||

| Confined water | Minimum of fluoride | 0.189 | 0.088 | 0.00019 | 0.00018 | 0.19 | 0.09 | ||

| Maximum of fluoride | 3.472 | 1.620 | 0.0035 | 0.0033 | 3.48 | 1.62 | |||

| Average of fluoride | 1.510 | 0.705 | 0.0015 | 0.0014 | 1.51 | 0.71 | |||

| Phreatic water | Minimum of fluoride | 0.0063 | 0.0029 | 0.000006 | 0.000006 | 0.0063 | 0.0029 | ||

| Maximum of fluoride | 4.40 | 2.05 | 0.0044 | 0.0042 | 4.41 | 2.06 | |||

| Average of fluoride | 1.38 | 0.65 | 0.0014 | 0.0013 | 1.38 | 0.65 | |||

| Confined water | Minimum of arsenic | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.0063 | 0.0029 | ||

| Maximum of arsenic | 12.075 | 5.634 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 12.09 | 5.65 | |||

| Average of arsenic | 1.621 | 0.756 | 0.0016 | 0.0016 | 1.62 | 0.76 | |||

| Phreatic water | Minimum of arsenic | 0.063 | 0.029 | 0.000063 | 0.00006 | 0.063 | 0.029 | ||

| Maximum of arsenic | 6.792 | 3.169 | 0.0068 | 0.0065 | 6.80 | 3.18 | |||

| Average of arsenic | 1.247 | 0.582 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 1.25 | 0.58 | |||